Fragmented Guardianship: Evaluating How Kafala & Wilaya Defined Privatized Gender Roles

By Fatema M.

Introduction

Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, International Labor Organization, and International Trade Union Confederation are a few of the organizations that have “named” Qatar as a state employing slave labor through kafala and have developed several reports to pressure the state into resolving the perils of migrant workers. The discourse around kafala is not used independently when discussing human rights violations, rather it is discussed and highlighted in conjunction to an array of human rights violations which include the violation of women’s rights. The question of women’s rights often references wilaya or guardianship, the roles and obligations of women within the household, domestic violence, and nationality laws. On the one hand, kafala is intended to regulate the rights of foreign or “guest-workers” within Qatar. On the other hand, wilaya is intended to regulate the rights of the family—women in particular. Both systems govern two different groups, and spaces—kafala governs foreign workers and the public space, while wilaya governs families, specifically women, and the private space. Although both systems appear to exist on opposite ends of a continuum, they appear to be interlinked, and perhaps have an impact on one another.

This paper aspires to explore the interconnections between Kafala and Wilaya, and how the adoption of the former system, impacted women governed by the latter system. This research seeks to answer: to what extent did adopting Kafala as a system impact Qatari women’s accessibility to the workforce? I argue that the adoption and institutionalization of Kafala solidified the private and public divide, further creating a narrative that legitimizes Qatari women’s roles as belonging to the private sphere. With the adoption of Kafala, women lost presence in the public sphere as it became occupied by more foreign workers and male Qataris leading the workforce. We see these practices continue today, as women entering the public sector require the permission of their guardians, the same way that foreign workers require sponsorship and permission to work in a specific job. I argue that the loss of presence in the public sphere is a symptom attributed to Kafala, and that in practice of Kafala and female guardianship, we see commonalities in the roles that women and foreign workers occupy.

The paper will look into Kafala in conjunction with Wilaya in two ways: the former looks at the guardianship of foreign workers, and the latter discusses matter related to the family, with specific mentioning of guardianship of women. By exploring these two legal bodies, I will look at how the women’s roles are shaped directly by family laws, and have similar practices resonating in Kafala. The objectives of this research are: (1) to explore the extent to which Kafala impact Qatari women’s economic participation; (2) to highlight similarities and differences in the treatment of foreign workers and Qatari women, by looking at the laws that govern their public and economic participation; (3) to analyze the ways in which women’s roles and economic participation changed before and after the oil boom, and how that led to the perceptions of women belonging to the private sphere in Qatar’s modern era; and (4) to discuss the implications that these practices have on women in Qatar.

Literature Review:

The literature review begins by contextualizing the roles that women occupied prior the oil boom in contrast to after the oil boom. By addressing these roles, the notions of the public and private will also be discussed. Then, the research delves into historicization of Kafala and the codification process. In this part of the research, I problematize how Kafala, and, consequentially, Qatar’s economic growth, resulted in actively dividing the public from the private sphere.

Roles of Women Prior and After Oil Boom

The roles of women changing over time are important to identify for various reasons. First, it allows researchers to define which opportunities for women remained as a signifier of heritage, culture, and tradition in contrast to which opportunities that cease to exist. Second, it allows researchers to contextualize the reasons why women’s employability is addressed in relation to women’s gender roles and social expectations. And third, although I would love to say it is one-step closer to taking down the patriarchy, understanding women’s economic roles allows researchers to understand the variations, degree, and extent to which patriarchal practices impact women. Thus, what are the economic roles of women in Qatar prior and after the oil boom?

The economic roles that women occupied prior to the oil boom were diverse; these roles were not representative of narratives of empowerment, equality, and women’s rights. Rather, these roles were necessitated by the social conditions that the society as a whole was experiencing. Within gulf societies, the main economic activities, “were centered on fishing, pearl diving, and trade. Pearl diving was the main industry and employed almost all the able-bodied men of the Gulf throughout the pearl-diving season, which lasted from June to October” (El-Saadi, 2012, p. 151). What remains quite interesting is that the pre-oil Gulf society was described as a “women society” (al-Misnad, year, p. 24; El-Saadi, 2012, p. 153). This description characterizes the period between June and October, where women were financially leading their households, while their “able-bodied” husbands were pearl-diving (El-Saadi, year, p. 153). The reliance on women’s economic activities was heavy as the pearl diving industry did not always guarantee a reliable income (El-Saadi, 2012, p. 153). Additionally, Bedouin women also had a significant economic role and assumed “direct responsibility for a considerable amount of tribal and commercial business” (Foley, 2010, p. 172; El-Saadi, 2012, p. 154).

Hoda El-Saadi explores the economic roles of women in the Gulf in two ways: gendered occupations and non-gendered occupations. Gendered occupations are specific jobs monopolized by one of the two genders, in which a member of the opposite gender partaking in this specific field, would invoke social unacceptance, stigma, etc. In the case of women, “All such services were well regulated and required the women practicing them to be skilled and rich in knowledge—the kind of knowledge that was not founded on formal education, but was actually passed on in the family by mothers and aunts (Rihani 28)” (El-Saadi, 2012, p. 154). In the case of Qatari women, much like Gulf women, the gendered occupations include: female teachers, muftiyat, midwives, wet nurses, hairdressers, beauticians (‘atshafa or hawaafa), and matchmakers (2012, p. 155). Other services included preparing brides for their wedding day and becoming a Dallala (female peddler) who “acted as an intermediary between the seller and the buyer; she would visit women in their houses and sell them goods, especially fabrics” (El-Saadi, 2012, p. 157). The dallala received a commission after every transaction. Although this job was portrayed as a gendered occupation by El Saadi, today, the dallala occupation remains gendered, but mainly occupied by men or dallals. Commonly, in Qatar, the dallal is not a Qatari, but is from a different nationality. Additionally, we see the over time, the occupation transitioned in to be occupied by men and also transitioned to include a specific class.

Non-gendered occupations include “services or products [provided] to both men and women” (El-Saadi, 2012, p. 158). These occupations include: healers, medical practitioners, zars, entertainers, salespersons, saqqa, and seamstresses (El-Saadi, 2012, p. 158-163). El-Saadi remarks by mentioning that these occupations had a direct impact on female life, in which many women catered their products and services to aid other women (2012, p. 163). However, their position within the Gulf economy remains integral, in which “[t]hey earned wages that were reinvested in the market, not only as they purchased their daily provisions or contributed to the family income, but through investment…in various ventures” (El-Saadi, 2012, p. 163). Allen Fromherz introduces other non-gendered occupations that Qatari women occupied, which included: women as pearl ship captains. After consulting with archives from Al-Khor Museum, Fromherz specifies that “there are accounts preserved at Al-Khor Museum north of Doha of all-female pearling ships and female pearl ship captains” who competed with the male pearl ship captains. The records he discusses address the legends of Ghilan and Mayy: “Mayy was a woman in competition with a man, Ghilan. The woman proved to be more competent, in the beginning, even in that difficult task of navigation and looking for pearl oyster banks. Man has been favored by destiny…” (Al-Khulaifi, 1990, p. 15).

The discovery of oil in the Gulf States: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman, drove the economic liberalization process following the “oil boom” of October 1973. (Winckler, 1997, p. 480) Although the Gulf States were primarily small, traditional, tribal Arab monarchies, the discovery of oil actively incorporated these states in the global market. The vast revenues attained through oil exports were directed towards the development of the different economic sectors of these states. (Winckler, 1997, p. 480) The discovery of oil in Qatar was discovered in two phases: the first was the discovery of the onshore Dukhan oil field in 1940, and the second is the discovery of the offshore field in 1960 (Sorkhabi, 2010). This was followed by economic liberalization policies in the 70s. In the case of women and their roles, we do not have significant records and archives addressing the roles they occupied. In “Papers of a Traveller in the Arabian Gulf” written in 1968, Hidayat Sultan Al-Salem stated:

Most women do not go out of their houses except on rare occasions. They go out to the market place once a year. Of course, women are completely secluded from men, they have their own social gatherings and parties. Mixing between the two sexes doesn’t exist at all. […] Radio and newspaper are the women’s only link with the outside world.

(Saud, 1984, p. 35)

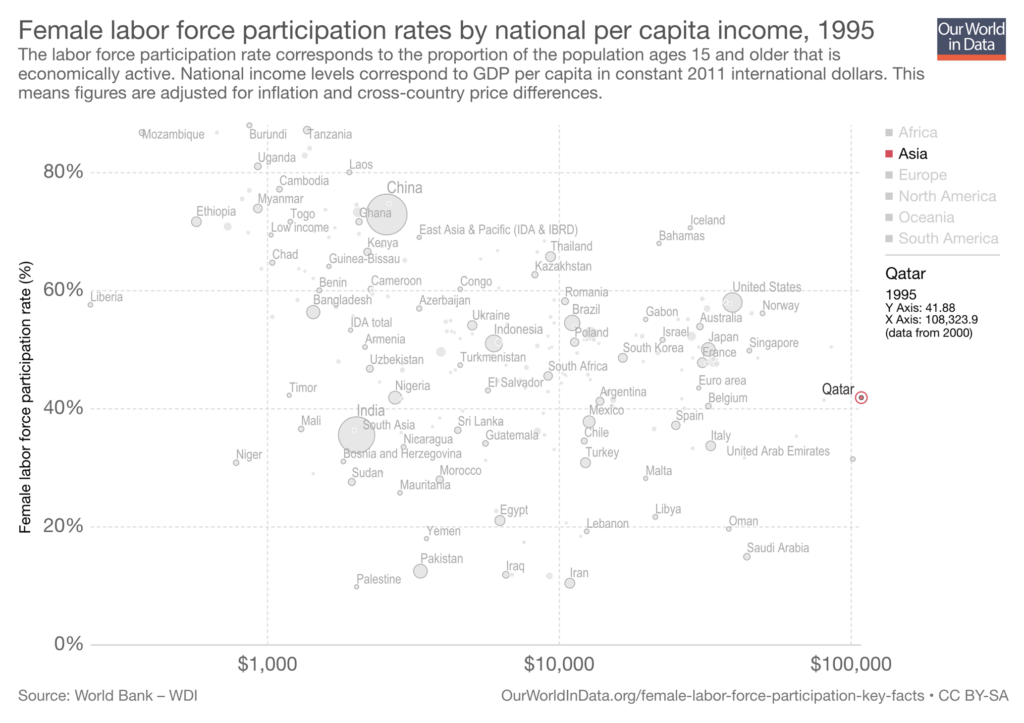

The roles of women, according to Al-Salem’s account, show that the realities of women are defined by segregation, in which their roles are privatized, existing solely within the private sphere—the household. Abeer Saud later shows that a higher number of women joined the workforce in the early seventies. However, their roles remained exclusive to education (Saud, 1984, p. 34). Comparatively, the World Bank data obtained on Qatari female labor force participation shows that in 1995, 41.5% of the labor force was comprised of women, as expressed in the below graph:

Graph 1: Female labor force participation, 1995:

(Source: Our World in Data, 2018)

However, it is unclear how much of that percentage is comprised from Qatari female nationals. This data suggests that Qatar is including more females within the workforce. The percentage slightly increased in 2005 with 43.45%, 2010 with 51.54%, and 2016 with 53.3%. A study conducted by At Kearney in 2016 showed that Qatar is the “best-positioned country” in the GCC with 51 percent female labor participation rate and only half of the female population over 15 years of age is economically active (At Kearney, 2016, p. 3). This data suggests there are economic activities that women are involved in but it does not express a distinction between Qatari women and non-Qataris and what roles they occupy.

Golkowska suggests that with the oil boom, new identities and narratives are being written: “As the national narrative is being written, new identities are being forged and traditional social roles renegotiated.” (2014, p. 58) Qatar’s economic growth “created intense strains between the old and new…[where modern] work patterns and pressures of competitiveness sometimes clash with traditional relationships based on trust and personal ties, and create strains for family life.” (General Secretariat for Development Planning 2008, p. 4 as cited in Golkowska, 2017). With economic growth, Qatar finds itself situated in a unique time and space, where “this conservative, gender-segregated tribal society ruled by sharia law prides itself on keeping close links to its past” (Golkowska, 2014, p. 59). Here, Qatar’s modernity still retains aspects of tradition and heritage, exemplified through the Qatar National Vision of 2030 which addresses gender equality, and individuals attaining their full potential: “enhance women’s capacities and empower them to participate fully in the political and economic spheres, especially in decision-making roles” (Golkowska, 2014, p. 59). Although the official narrative stipulates women’s visibility within the public sphere, there appears to be constraints that prevent this visibility to materially and socially achieve its potential. These constraints are defined by the family laws and specifically the notion of wilaya and guardianship.

In 2006, Qatar promulgated its first personal status law “which regulates family matters such as inheritance, child custody, marriage, and divorce” (Sonbol, 2012, p. 334). Personal status laws are “what differentiates one human being from another in natural or family characteristics…such as whether the human being is a male or female, married, widowed, or divorced, a father, or legitimate son, a full citizen or less by reason of age or imbecility or insanity, and whether he has full civil competence or is limited as to his competency for a legal reason” (Sonbol, 2012, p. 334). The notion of guardianship or wilaya became codified within the family law, which regulates the rights and privileges a female Qatari citizen is eligible for in the private sphere, and also how their rights in contrast manifest in the public sphere. The argument of guardianship is derived from the Quranic verse: “Men are the managers [qawwam] of the affairs of women for that God has preferred in bounty one of them over another” (Qur’an, Surat An-Nisa, 34 as cited in Sachedina, 2009, p. 140). The verse from Surat An-Nisa functions “as a major documentation for curbing a woman’s empowerment more directly in domestic life, but also indirectly in public life” (Sachedina, 2009, p. 142).

Wilaya here references managing the affairs of women, and focuses mainly on their obligations within the household. However, legally, women are required the permission of their guardians to travel, and to be employed. The law specifies that women under the age of 25 are required their guardian’s approval to obtain a driver’s license, to travel, and to work. However, practice dictates otherwise. Based on informal conversations I have had with Qatari women, Qatari men, and expatriates, I found that the practice of wilaya remains prevalent even after a woman reaches the age of 25. In one discussion, a Qatari man expressed that depending on the family’s belief system and how “liberal” they are, most women are expected to fulfill their familial roles prior to their social and public roles. In public, women are expected to retain their social expectations that exist within the household. The family law, regulating the employability of women, further suggests that women’s employment is a concern that is extended from their roles within the privacy of their homes. The law specifies that the obligations of a women in a marriage are centered around the household, and the family structure.

Thus, it is important to establish a distinction between law and practice. The codification of family law has been actively and widely delved into by scholars. However, the practices of guardianship remain undocumented. This perhaps extends from the problematic nature of the obligations and entitlements imbued within the family law in Qatar. On the other hand, practice suggests that women’s roles in the public space are not defined through employment or their social presence, but are rather conditioned by their family law obligations. How do we explain the roles of women as monopolized primarily by their obligations within the private space? In this study, I suggested considering the way in which Kafala came about and how it regulates the public sphere, and the fact that the Qatari population is now exposed to a larger group of migrants and guest-workers, the nuclear family within the Qatari social fabric rose in importance. By extension, women’s obligations to the nuclear family are further accentuated by the codification of family law, and their invisibility in sources collected from in the period following the oil boom.

History of Kafala: From Practice to Codification

According to a representative of the National Human Rights Committee, “The sponsorship system started in 1963. It appeared at that time as a regular humanitarian law which allows the foreigner to be protected by this the Qatari citizen and also guarantee the government [the ability] to observe and monitor the foreigners in the country” (Hubail, 2015). This is seen through Law No. 3/1963 which regulates the “Entry to and Residence in the State of Qatar by Expatriates” (Qatar Ministry of Labor, 2018). The discovery of oil in the Gulf States, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman, also called the “oil boom,” drove the economic liberalization process of October 1973 (Winckler, 1997). Although the Gulf States were primarily small, traditional, tribal Arab monarchies, the discovery of oil actively incorporated these states in the global market. The vast revenues obtained through oil exports were directed towards the development of the different economic sectors of these states (Winckler, 1997, p. 480). The Gulf States were small in size, with a cumulative population of no more than 6 million in 1975 with the majority of that population residing in Saudi Arabia. So, the economic liberalization process necessitated the reliance on foreign labor, in which “one person, one Qatari citizen suddenly becomes responsible for thousands of people when it used to be only [a] few people—10 or 20 or 100 maximum. Suddenly, they own big companies and [become] responsible for thousands of people” (Hubail, 2015). The GCC countries had a small workforce population and conversely many South Asian and Southeast Asian countries had large populations with high unemployment rates. Thus, the push-pull factors between the home and host societies drove the migration to the GCC.

According to Onn Winckler, a professor of Middle East History at the University of Haifa, as the Gulf States experienced an exponential increase in the mass migration of foreign laborers, they resorted to employing measures that would prevent foreign laborers to permanently reside in the host-country, and maintain the national population as Arab (Winckler, 1997, p. 484). Consequentially, the Gulf States created a system of temporary guest-workers, one that required each immigrant to be sponsored by a national in order to work in the state, a system denoted as Kafala. Steven D. Roper, the Dean of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Nazarbayev University, and Lilian A. Barria, a professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University, explore the variation in the implementation of kafala across the Gulf States to understand the factors that “contribute to the differences in kafala policies” (2014, p. 32). In their analysis, the scholars explore the kafala system as a government tool to regulate labor flow and monitor the activities of workers. Like Winckler, they conclude that kafala cannot be explored independent of the nationalization programs that each country is introducing.

Between Kafala and Wilaya: The Question of Women’s Workforce Participation

Kafala is a customary practice, but exists under the guise of the labor law which defines the various ways in which sponsorship of foreign workers can be taken in Qatar. The question of kafala raises important concerns. First, it regulates the activities, rights, and entitlements of foreign workers. Second, it places foreign workers under the sponsorship of a Qatari. Third, since Qatar’s economic activities are built on foreign workers contributions to the state, it further situates a dividing space between foreign workers and Qataris. These concerns place kafala as primarily a practice concerning the public space, one which has some private aspects to it such as the living conditions that foreign workers are entitled to, but mainly regulates the activities of foreign workers in public as economic contributors. In context of how kafala came about, it is important to understand the implications that the practice and the sponsorship systems had on the remainder of Qatar’s social fabric—mainly Qataris. According to Sonbol:

Nation-state building brings about transformations in all aspects of life, including the economic, social, and cultural. The appearance of the modern patriarchal family is perhaps the most significant development for women, particularly because of the accompanying changes in the legal system brought about through the nation-state building process. The needs of centralizing national governments meant the promulgation of standardized laws and their implementation in a homogenized and equal fashion among their peoples. (Sonbol, 2012, p. 21-22)

Here Sonbol highlights how states constructing a national identity and narrative often have to undergo changes internally. In the case of Qatar, we see the construction of the national identity lead to the development of standardization of laws and codifying them, such that the spaces occupied by Qataris and non-Qataris, whether public or private, are regulated, monitored, and seemingly protected by law.

However, the development of kafala and wilaya express a division within the state, rather than an expression of homogenization. On the one hand, kafala solely applies to foreign workers. The fact that the labor laws address the economic contributions and the work of foreigners in Qatar, places them mainly in the public sector, where their contributions would have an impact on the country’s national income. On the other hand, the female fragment of the Qatari population also have labor laws governing their work locally, but practice renders them as mainly constrained to the private space. This is mainly attributed to wilaya. In the case of wilaya, customs and practice do not reflect the legal system of family laws only governing the private space. Instead, we find cases of different practices that attempt to impose wilaya on women, even within the public space. What we find here is a convergence between the public and private space. Women have rights granted to them by the labor law (although some are insufficient or vague), but wilaya renders women as primarily requiring the permission of their guardians. For example, in an interview conducted with a Qatari female civil engineer in November 2017, the interviewee stated that she requires the permission of her guardian to work in the male-dominated field of civil engineering. She was asked multiple times in her employment interview if her family would allow her to work in a construction site, mainly because it is seen as a gendered occupation dominated by men. In the case of this Qatari female interviewee, the requirement for wilaya, in her opinion, stems from two grounds. First, the sector she is entering into is one dominated by men, specifically foreign workers (construction workers). This was further seen as presenting a threat to the female Qatari, as she is not socially expected to interact with this segment of society. Second, the requirement for the permission of her wali, although she is above the age of 25, further entails that women remain constrained by their gender identities, and by extension their gender expectations. These gender expectations are not just limited to Qatari women. In fact, non-Qatari women who are employed by public institutions continue to require the permission of their guardians, prior to employment—a requirement that men do not have to adhere to. Thus, what we see here is that the development of the Qatari nation-state, led to the institutionalization of laws and practices that divided the society into Qatari and non-Qatari, male and female. Each binary comes with its own set of roles and expectations. Women, primarily Qatari women, remain defined, constrained, conditioned, and governed by the family law. The same practices are diluted in the cases on non-Qatari women, but remain prevalent there as well.

Conclusion

In the case of women and employment in Qatar, we find a disruption in their public participation, one that did not historically exist. In the past, as mentioned earlier, women occupied both gendered and non-gendered occupations. Through my discussions with Qatari women, I found that some women avoid mentioning that they are entrepreneurs, successful businesswomen, and often require the permission of their families before venturing into unconventional jobs. There does not appear to be a direct correlation between wilaya and kafala. However, when we contextualize both in relation to Qatar’s state-narrative, and the nation-building process, it appears that both systems function to regulate different spaces. In the case of wilaya, it appears to continue resonating in the public sphere, and continues to condition women to fulfill specific gender roles and expectations throughout their employment. This is not necessarily problematic, because women could be abiding by these practices out of respect for their culture and their families. However, it situates women within the cultural and patriarchal constrains that continue to define what they can or cannot do, what jobs they can or cannot pursue, and how they can or cannot behave.

In the case of Kafala and the subsequent institutionalization of the practice through labor laws, we find the labor expectations of women continuing to be tied to the importance of satisfying their guardians, and protecting women as they are seen as the guardians of morality. The Qatar National Vision 2030 accurately conceptualizes this conflict between modernization and tradition as it states, “modern work patterns and pressures of competitiveness sometimes clash with traditional relationships based on trust and personal ties, and create strains for family life” (General Secretariat for Development Planning, 2008, p. 4). However, it continues to stress on the requirement for families to remain strong, care for their members, and “maintain moral and religious values and humanitarian ideals” (General Secretariat for Development Planning, 2008, p. 22). Thus, this presents women with two conditions: if they pursue their economic aspirations, it needs to be with the permission of their guardians; and if they are within the public space, they must maintain the ‘moral’ and ‘religious values’ of the state. Qatari men are not explicitly tied to the morality and religious values of the family or state. Rather, the family law places women as the primary guardians of morality and religious values, as men retain their place as guardians of women. This study focuses mainly on how the privatization of women’s roles, their family law obligations, and subsequently the codification of the family laws are an extension of Qatar’s oil-boom, economic development, and reliance of foreign workers.

This research has some limitations that must be addressed. Primarily, there are not significant or accessible archival sources that explain the discourse and narratives around the adoption of kafala, the labor laws, and the family laws. Thus, the connection between kafala and wilaya requires more research, interviews, and the establishment of direct connections and distinctions between both. In addition, it is important to distinguish how wilaya changes between Qataris and non-Qataris to see which resonates more within the employment sphere. Lastly, it is important to look at the labor laws and the family laws as a holistic and comprehensive system, which functions at different levels and different ways. Thus, the laws need to be seen in context of how they were written, to understand the implications that these laws have on those governed by them. The visibility of women within the public space remains conditioned by the family laws that govern them, and are further accentuated by the perceived threat of foreign workers on the family structure in Qatar. The question that remains to be answered is: are kafeels defining, controlling and conditioning the roles of foreign workers in the same manner as the walis in relation to women?

References:

Golkowska, K. (2017). Qatari Women Navigating Gendered Space. Social Sciences, 6(4), 123.

Golkowska, K. U. (2014). Arab Women in the Gulf and the Narrative of Change: the Case of Qatar.

Hubail, Fatema. (2015). Interview with a representative of the National Human Rights Committee. NHRC. Qatar.

Kearney, A.T. (2016). Power Women in Arabia: Shaping the Path for Regional Gender Equality. Online.

Onn Winckler, “The immigration policy of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states,” in Middle Eastern Studies 33.3 (1997): 480-493.

Our World in Data. (2016). Female labor force participation rates by national per capita income. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/female-labor-force-participation-rates-by-national-per-capita-income

Qatar Ministry of Labor. (2018). “Law No. 3 of 1963 concerning the Regulation of Foreigners’ Entry and Residence in Qatar (Repealed).” Qatar Ministry of Labor. Retrieved from, http://www.almeezan.qa/LawPage.aspx?id=2595&language=en.

Qatar, G. S. D. P. (2008). Qatar National Vision 2030. Doha, General Secretariat for Development.

Roper, S. and Barria, L. (2014). Understanding Variations in Gulf Migration. In Middle East Law and Governance, vol. 6.

Sachedina, A. (2009). Islam and the challenge of human rights. Oxford University Press.

Saud, A. A. (1984). Qatari women, past and present. Longman Publishing Group.

Sonbol, A., & Dreher, K. (Eds.). (2012). Gulf women. A&C Black.

Sorkhabi, R., & Morton, M. Q. (2014, January 21). The Qatar Oil Discoveries. Retrieved from https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2010/01/the-qatar-oil-discoveries